07 Dec Little Bird

This concludes the weekly blog posts on each track from my album Dream of Home. My post on the title track is a good place to start to get properly introduced to the series.

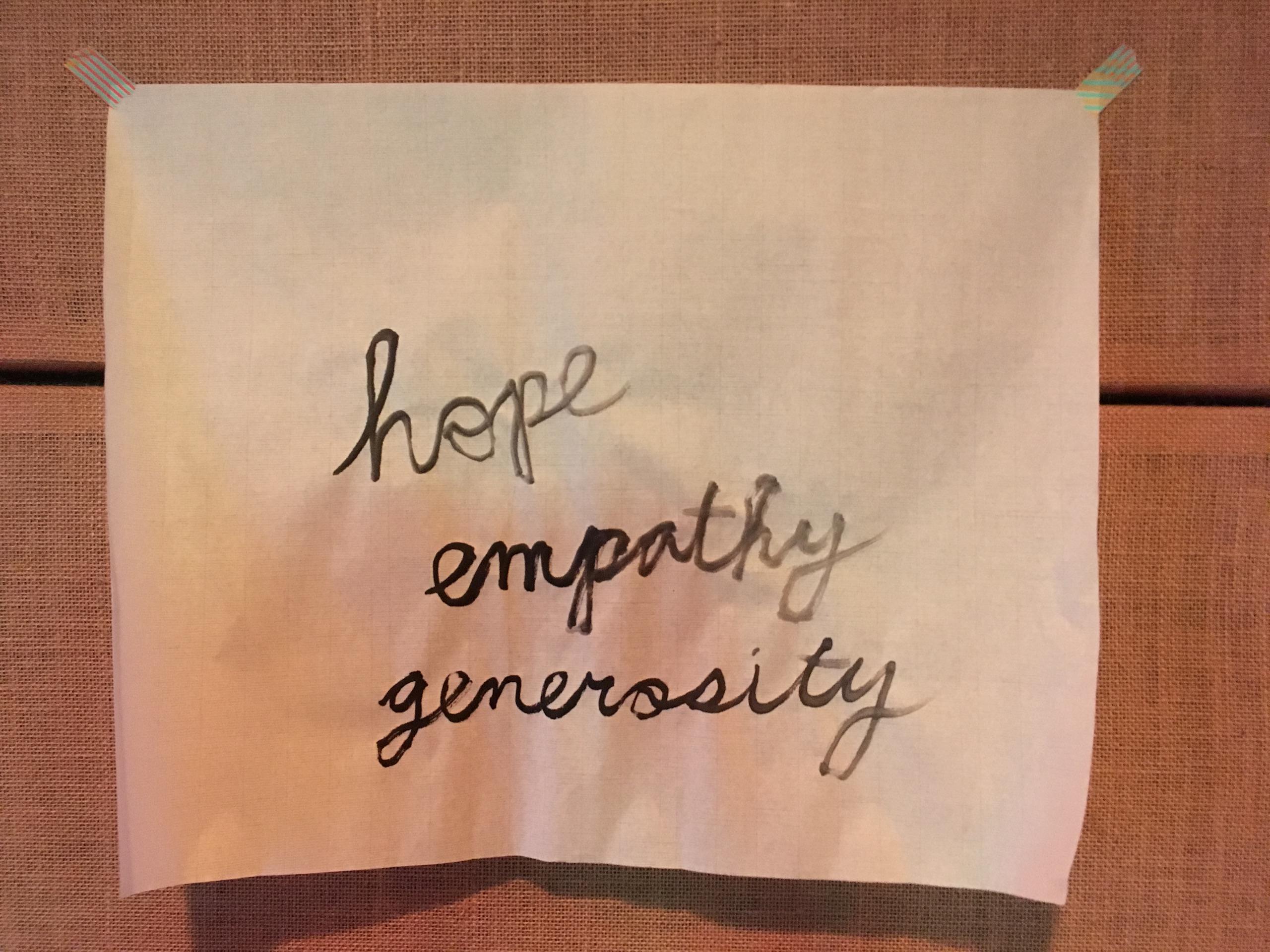

Jebi, swallow … any little bird

My old friend, HeeSung 언니, who produced and directed the music video above, told me that the reason that Korean food includes lots of roots and plants—which happens to be on trend these days with people into well-being and healthy living—is because Korea was dirt poor after the war and people had to forage for food. My song “Little Bird,” and more broadly, my singing with gayageum, were also born out of necessity. I had hoped to accompany myself on gayageum someday but imagined it would happen if I got around to learning to play the modernized gayageum. But without a piano in Korea, I turned to my 12-string traditional instrument for accompaniment and started arranging songs as a fun exercise. My gayageum teacher Yuny 언니 asked if I would perform a song called 제비가 돌아왔네 “The Swallow Has Returned” for her show at the beloved Hongdae venue 제비다방 Jebidabang, which means “Swallow Cafe,” and HeeSung 언니 liked my arrangement so much, she insisted on making me a music video.

The swallow/jebi song is from and popular among the numerous ethnically Korean Chinese in 연변 Yanbian and while it sounds like it could be a folk song, it has a composer and lyricist. We weren’t able to track down the rights to record it so HeeSung 언니 told me to write another song about another little bird, any little bird. So I wrote “Little Bird.” HeeSung 언니 smuggled me in to the radio station she worked at to cut the solo recording and then I needed to hire someone to mix it so I asked Ross if he can do simple mixing and he said, “Have you talked with Nick?” (meaning our trombone Nick). Then I asked Nick and I think he said, “Have you talked to Ross?” Gotta love those two.

Ross ended up mixing the recording and encouraged me to make an album, saying he’d produce it. I was as enthusiastic about the idea as I was about making the music video, which is to say, indifferent in the throes of grief and sadness. It’s good to have proactive friends like HeeSung 언니 and Ross that push you forward when you just want to lie low. HeeSung 언니 not only recorded the audio for me but blocked out a weekend for the music video shoot, booking the camera guy, a traditional hanok-style hotel, and a show for me, declaring herself my manager. Her only request was that I come with eyelash extensions so I dutifully got my first set of lash extensions, doing the least I could, which was the most I could manage at the time. In short, the whole album grew out of this little song.

Little bird says “What’s going on?”

I had written the song less than a year into my stay in Korea, while I was still hopeful and not completely crushed, though I had long since recognized that it wasn’t the home I thought I knew. The lyrics speak to the experience of leaving your homeland then returning, full of hope and sweet memories, momentarily forgetting that there was a reason you left. In my experience, once you leave a place, be it a country or city, you can never return; you can physically go back, of course, but people will have moved on, you will have changed, and everyone will be in a new stage of life. A word of caution: returning may break your heart. This song is about the state before heartbreak and the empathy shared among those who have returned home and found themselves wide-eyed, wondering, “What’s going on??”

Vibe control and quality control

During the recording sessions, I claimed the role of vibe control, making sure we didn’t get bogged down with musicalities over the story, over the essence. At the same time, I took copious notes on mixes and versions, and checked and double-checked minutiae, so I find it hilarious that I only noticed I didn’t sing the final verse lyrics “As you spread your wings and fly” months after it was complete.

Quality control was guaranteed by virtue of the musicians playing on the album. Ross joked that he put together the softest band for my album and I’m happy with that. There are exceptional drummers, pianists, etc. who swing, play in the pocket, and are a thrill to listen to but if they don’t also play with nuance when playing soft, they would not be suitable for my music. Also, I’m a stickler for pitch but it didn’t occur to me that I was singing the chorus (the part that goes “쑥국 ssuk guk” quoted from the Korean bird song 새타령 “Saetaryeong”) deliberately under until Ross pointed it out, saying he figured it was a sort of blue note in Korean music. I grew up hearing “Saetaryeong” and the folk song obviously was not made to fit the well-tempered piano, and so I must have had the melody in my head with its microtones and never given it a second thought.

Make music, not war

When I released the solo recording with the accompanying music video, I heard there were people who were vocal with their concern for the way I was resting my gayageum, with the bundle of rope (I think of it as the hair on the gayageum) up. They were displeased that this expat didn’t know how to properly hold a gayageum and I had two thoughts in response: It’s great that strangers care enough to actively dislike what I’m doing and actually, I am holding/resting the gayageum in the old-school way.

My late gayageum teacher taught me that the hair side, the end with more delicate ornamentation, should be up when resting the instrument against a wall. She had immigrated to the US and kept to her old ways while musicians in Korea got stronger glue to hold the instrument together and turned the instrument upside down (or right side up, depending on how you look at it.) I would always rest it the way my teacher taught but didn’t care how I held it while standing and would go either way. But when I was invited to go on and snap a photo at the 국악 traditional music radio station, I deliberately put my gayageum hair up, as a metaphorical middle finger to the haters. Then I felt guilty, not about offending anyone, but about what my late teacher would think about me using her instrument with malice. I decided not to use it like a weapon again; the gayageum should be an instrument of peace.

Expat life

Oftentimes, it’s those who leave their homeland who cling most tightly to traditions and antiquated practices. I recall reading about Soviet Koreans, who immigrated long ago and have preserved traditions that Koreans on the Southern half of the peninsula don’t practice anymore. It’s the occasional Korean outside of Korea still calling “butter” 빠다 (bbah-dah) instead of 버터 (buh-tuh), which sounds closer to “butter.” My dad, who left Korea in the early ‘90s and has a tendency to use outdated, country Korean, would say 빠다 if the word ever came up (Korean kitchens don’t use butter and men are scarcely found in the kitchen). My mom, who is more up to date on linguistic transformations, has said she can’t be sure of Korean spelling because the governing body keeps changing it. How are expats to keep up? And are we more Korean in a way than those who stayed in Korea?

One final reflection on being an expat: My college composition teacher used to say that the weight of history (i.e., Beethoven) is tremendous for German composers in writing for string quartet while their American counterparts have no such history to reckon with and can do whatever they want, essentially. I sense that this is also true for Korean musicians. Korean traditional musicians may have an underlying sense of obligation to uphold tradition, while an outsider like me, a Korean American, feels free to do whatever, while hopefully still respecting the music.

Today marks one year since I released my album and I’m glad that I’ve now had a chance to write on each track off Dream of Home. Thanks for reading and happy holidays! And check out the music video—it has beautiful translations in a dozen languages from friends who understand what it’s like to be expats.

__

Find Dream of Home on YouTube Music, Bandcamp, Apple Music, Amazon, and Spotify.

No Comments